This is an except from the SartRE + sARTre feature about Tarkovsky.

A Cold War chiller – investigating Tarkovsky’s camer(a)lchemy in the opening of Veronica Swan’s Still Life.

To revisit the film locations of Veronica Swan’s Still Life, where the movie bled into the real world, was to court a certain spectral echo, and yet we dared to poke the ghost, however, we had not anticipated a literal reenactment of its celebrated high-speed pursuit. In Swan’s unsettling tapestry, a crimson automobile emerges from the Cold War edifice nestled beneath the skeletal grace of the Great North Road’s radio transmitters – that ancient artery threading London to the North, a once pulsing vein which fell victim to the vampire teeth of the new A1 Motorway. For those forever captivated by the film’s opening, those who have pondered its intricate mechanics, asking how the unseen gears might possibly drive Swan’s dark chariot; we ventured forth on your behalf to unearth its secrets, digging in the soil by the swallow holes, though certain balletic camera movements still defy rational explanation to this day. It was, famously, a single, unbroken shot, the camera itself a bespoke marvel, procured by the enigmatic Tarkovsky, a veteran of legendary cinematic moments, including the final, lingering gaze of Antonioni’s The Passenger, (the alias under which a teenage M.J McCarthy Jnr, one of the shadows behind the Still Life soundtrack, released an early cassette, recorded in the 1980s on Warrengate Road, the location of the legendary ‘swallow dive’ scene, which we cover in our feature about THE REGAN TAPES).

Veronica Swan, of course, turns the temperature way down on the Cold War, a thriller becomes a chiller in the hands of the caped Queen of Doom who claimed Tarkovsky’s camer(a)lchemy, as she trademarked his style, could only have come at a price, a Dostoyevsky card game with the devil, transported to the crossroads by the transport cafe below the pylons or his favourite watering hole (DROP IN FOR A LIBATION).

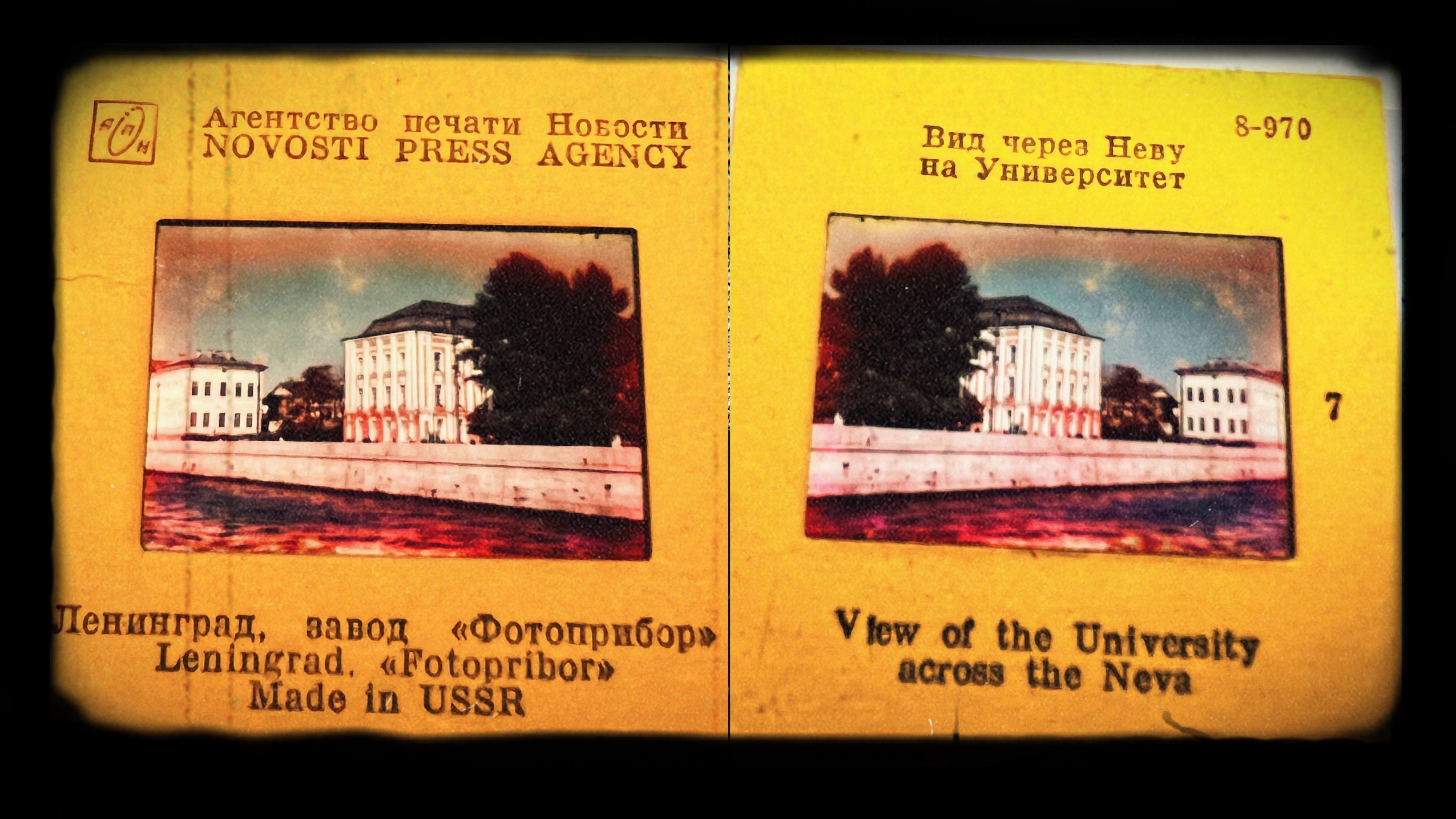

Our initial foray to the opening location was met not with cinematic wonder, but the brusque demand of security to kill the camera and surrender the captured ghosts. The blunt welcome as subtle as a Soviet concrete block, which was why we tried to film it using our backup eye, until they clocked that too. Unwilling to witness the digital erasure of our secret shots, we found ourselves embroiled in an impromptu high-speed drama of our own, a page ripped right out of the movie script, tyres burning the same corners, a desperate attempt to outpace our pursuers along the very route etched into the film’s opening sequence. Spoiler alert: they prevailed, and our last bit of visual truth vanished into their black hole van. Hence, the accompanying images are rare remnants, two of Tarkovsky and Swan’s own location photographs. To the left, the stark geometry of the building as the red car materializes, the camera descending from the colossal transmitter, seemingly liquefying through the windscreen as the first flakes of snow begin their ethereal descent, as if we have just shaken a snow globe scene. To the right, Swan’s lens captures the skeletal transmitters looming over a field where horses graze, the last vestiges of habitation on Dellsome Lane, framed against the hill where the moment of explosive climax will unfold in the film’s opening. The red car, receiving a disembodied radio command, seems to defy physics, hurtling towards the bumper of a police patrol car, its lights a frantic pulse against the encroaching dawn and the swirling snow. The viewer’s perspective then executes an impossible ballet, gliding through the red car’s windscreen, through the police car’s rear window, between the silent figures within, and finally through to the vehicle they are both relentlessly pursuing. This, then, is our abrupt immersion into the disquieting world of Veronica Swan’s Still Life. We already possess enough screen action for more than one in depth feature series, and yet, we have barely scratched the surface. Mr. Tarkovsky is poised to unlock his box of cinematic sorcery… but first, let us trace the origins of those beguiling illusions. Perhaps our readers can help us in the search. There is one particular slide we have been trying to locate which is missing from the archive.

It is from the Novosti Press Agency. The slide says Leningrad, Fotopribor, Made in USSR. On the reverse of the slide it says View of the University across the Neva River. If any of our readers can locate it we will gladly offer a reward.

LOST AND FOUND. Have you seen this slide? Email a photograph of the slide and your scented cassette to [email protected] to claim your reward.

Mention post-war Vienna, and the mind’s eye conjures immediate cinematic tropes: the chiaroscuro of subterranean shadows, clandestine encounters against the melancholic grandeur of the Ferris Wheel. Carol Reed’s Third Man cast a long enough shadow to touch a young Ivan Tarkovsky, who found himself in the city in 1958 as a participant in the Seventh World Festival, a carefully orchestrated Soviet propaganda spectacle. Young Ivan, a student eager to disseminate his knowledge of officially sanctioned Russian literary figures, would have certainly omitted one particular title: Doctor Zhivago. His burgeoning association with Pasternak’s forbidden masterpiece rendered him a target for the unseen machinations of the CIA. They had, in a misguided attempt – ill-advised, according to MI5, who cautioned against endangering Pasternak himself and conveyed their concerns to Tarkovsky during their own discreet approach in 1958 – printed their own clandestine copies, a Russian translation intended to be smuggled back into the very nation that had banned the debut novel of one of its most revered poets. In 1956, Ivan had journeyed to Italy, ostensibly to observe a scriptwriting session for Tolstoy’s sprawling epic War and Peace, but his interest was also piqued by the publication of an Italian edition of Zhivago by a small, left-leaning publishing house. It was on this trip that he encountered Carlo Ponti, the tenacious producer who had finally shepherded the War and Peace project to fruition after numerous attempts faltered due to a lack of Soviet endorsement. Ponti envisioned Zhivago as a future vehicle for Sophia Loren, his soon-to-be wife. Tarkovsky’s association with Ponti blossomed, leading to his involvement in a number of significant films, including Agnes Varda’s enigmatic Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), the sweeping romance of Doctor Zhivago (1965), and the existential enigma of Antonioni’s The Passenger (1974). His collaboration with Veronica Swan commenced in 1973 on her award-winning exploration of Mary Queen of Scots, a film largely brought to life in the atmospheric environs of Elstree and the stately grounds of Hatfield House and Hatfield Park, mere yards from the very Cold War edifice that looms in our earlier image, a silent witness along the Great North Road.

What began as a seemingly straightforward exploration of the camera techniques employed in one of our cherished films has spiralled into a labyrinthine inquiry, touching upon the highly clandestine endeavors to breach the sound barrier. The jet test experiments conducted at the De Havilland aircraft factory in Hatfield were, at the time, at the very vanguard of aviation technology. Geoffrey de Havilland’s son, Geoffrey Jnr, indeed holds the tragic distinction of being the first to break the sound barrier in the DH108 Swallow. Taking flight from Hatfield, soaring over the familiar landscape of Hatfield Park, veering to avoid the looming transmitters, it reached the elusive Mach 1, only to claim the test pilot’s life in a catastrophic disintegration over the Thames. A thunderous boom echoed across the countryside, rattling pylon by pylon back to Hatfield, accompanied by reports of strange lights trailing the doomed aircraft’s path. Eyewitness and earwitness accounts meticulously documented in the accident report led the de Havilland team to the grim conclusion that the sound barrier had indeed been breached, but severe and violent longitudinal oscillations preceding the aircraft’s breakup had forced the pilot’s head with fatal force against the cockpit canopy. Another test pilot had encountered the same perilous instability, returning prematurely, just shy of that elusive speed. His nom de guerre: The Very Best. The tale goes thus, Geoffrey de Havilland Snr, in a moment of pride, and perhaps a touch of dark premonition, had gestured towards this pilot, declaring, “We don’t just want the best, we want the VERY BEST,” laying a hand on the shoulder of the man destined to inherit the mantle. The Very Best fathered a son who, too, embraced the perilous skies as a test pilot, the simple inscription THE BEST stitched onto his flight jacket. He, in turn, had a son known simply as BEST.

What, one might reasonably inquire, does this tangled web of obscure and potentially irrelevant information concerning secret jet testing have to do with the aforementioned car chase sequence? The answer, perhaps, lies in the identity of the driver of the vehicle being pursued by the crimson car and the Police car: it was THE BEST, code named MERCURY, the test pilot who, in the year 1973, vanished in a puff of smoke – an incident that, two decades later, would become the spectral heart around which Veronica Swan so meticulously painted her haunting Still Life.

If you’d prefer to have Still Life read to you by Austin Inisheeran… press play on the Still Life tape below. AudioAssembly from the WoodWard, exclusively created for AromaSpace.

The high speed chase took a turn at BALLOON CORNER https://w3w.co/deeply.star.monks where Vincenzo Lunardi landed his hot air balloon.

To continue on with this feature select TARKOVSKY A1 A2

Or follow the A1 thread to THE REGAN TAPES A1 A1

Or return to NOW SHOWING